(TAXING) THE BIRD IN THE HAND… AND THE TWO IN THE BUSH?

Read more

November 7, 2025 | 4 min read

Author: Andy Wood

Introduction

As I’ve said before, the most popular taxes are those paid by other people.

Survey after survey confirms it. The one exception, oddly enough, is inheritance tax. A tax hated by almost everyone, despite the fact most people will never actually pay it.

So, perhaps it was only a matter of time before someone suggested taxing robots and AI.

Surely this is a tax proposal we can all get behind?

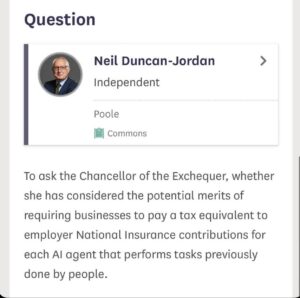

An interesting Parliamentary question

Last week, Neil Duncan-Jordan, independent MP for Poole, asked whether businesses that replace human workers with AI agents should pay a levy equivalent to the rate of employer’s NIC.

An interesting question… and one that forces us to think hard about how tax, technology, and society interact:

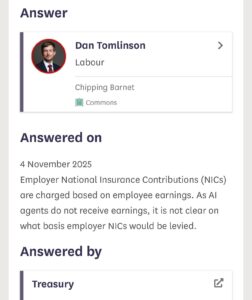

An uninteresting answer

An interesting question, deserves an interesting answer.

But, it being modern day Westminster, it obviously didn’t get one

And plenty of things to think about, whether one is for, against or on the fence.

However, the government’s response was disappointingly beige and, may I say, a little obtuse:

Of course, there was nothing in the original question suggesting that NIC should be imposed on AI. Instead, my reading of the question was whether a new tax, set at an equivalent rate to NIC, might be levied in such circumstances.

The hollowing-out of the tax base

What’s the issue?

Well, the UK’s tax system currently depends deeply on human participation.

Indeed, income tax and NICs are the heavy-lifters when it comes to plucking feathers from the UK’s taxpaying geese.

If businesses replace large swathes of their workforce with machines, it seems a fair consequence that, in the absence of any response, those revenues will be decimated.

Corporation tax would, in a wholly static world, plug the gap as great costs would be taken out of the business and profits would soar.

However, surely AI will be deflationary?

The price of goods and services where AI is utilised (and human labour removed) will become cheaper and cheaper?

Where profit margins are broadly kept the same, then the Exchequer gains little from taxing corporate or business profits.

Of course, where one is employing lots of people, in big offices, then one is certainly creating a taxable base in a jurisdiction.

But what if companies can exist with a skeleton staff, who themselves can work more remotely?

Might, they look at where they operate from in the world. Our robot friends working from hammocks on Caribbean beaches?

As such, international tax reform will certainly need to factor this into the equation.

The paradox of taxing progress

A “robot tax” sounds self-defeating.

If technology makes work cheaper and output faster, why blunt that progress by adding a new cost?

But we already tax activities with negative side-effects – pollution, tobacco, sugar.

Perhaps automation’s externality isn’t smoke or soot, but unemployment?

Even so, a poorly designed levy could stifle innovation and spark a new kind of tax arms race, where firms relocate to friendlier regimes.

As ever, coordination will be key: a global economy demands global solutions.

Humans without work

Tax is only one part of the problem.

The deeper question is social: what do people do in a world where machines do almost everything?

How will people earn, spend, and find purpose?

Does a Universal Basic Income or “AI dividend” become inevitable?

Or does technology simply create new industries, as the machines of the Industrial Revolution once did… albeit after a potentially painful transition?

Even in the most optimistic scenario, there will be winners, losers, and time lags.

Skills will need rebuilding. Incomes will need bridging. The tax system will need to adapt to support that journey rather than simply obstruct it.

What do you think?

Would a “robot NIC” be a fair way to share the spoils of automation…

… or simply an attempt to levy a tax on progress?